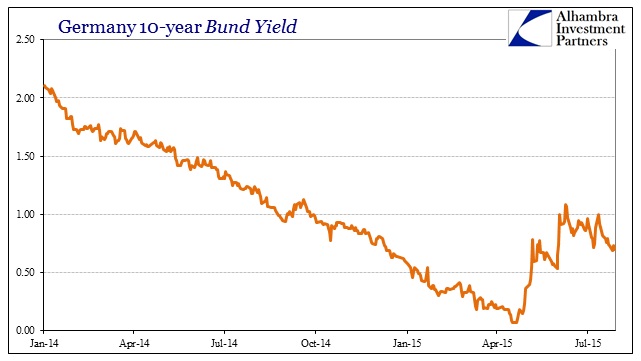

The simple narrative about QE is drawn from what is believed a simple process. The central bank buys bonds and by doing so it is simply assumed to be an “extra” bid on bond prices; therefore interest rates fall in whatever issue is being targeted by QE. Even in the US, QE has had trouble with that simple relationship. Instead of being a straightforward, easy to see and direct correlation the best the FOMC can come up with is some statistical relationship about “term premiums.”

Despite some nice jargon harmonized about them, term premiums are the simple conjuring of economists trying to grasp why markets aren’t always “rational.” To illustrate this point, Ben Bernanke in April wrote up within a multi-part series about why interest rates recently have been so confounding against his monetary genius (in QE, of course).

For example, in the US, ten-year Treasury yields have fallen from around 3 percent at the end of 2013, to about 2.5 percent during the summer of 2014, to around 1.9 percent today. The recent renewed decline was unexpected by most observers, including me. Why are longer-term interest rates so low? And why have they fallen even further recently, despite signs of strength in the US economy?

Term premiums seem to be the answer where bond markets do the opposite of what policy intends and even demands. During the period Bernanke cites above, the FOMC was actively tapering QE and yields continued to fall, indeed all the way past the point where QE actually ended. This uninhibited behavior is not unlike, in nominal expression, the period during Greenspan’s “conundrum” in the middle of the last decade.

Bernanke again:

Alan Greenspan’s “conundrum” of 2006, when the Fed raised short-term rates but long-term rates didn’t follow, appears to have been the result of an unusually low term premium, as can be seen in Figure 3. The “global saving glut” and the associated demand for Treasuries by foreign central banks and sovereign wealth funds may account for the low value of the term premium around 2006. Reduced uncertainty about the course of interest rates, as indicated by the low value of the MOVE index in 2006 (Figure 3), was likely also a factor.

In other words, he has no idea. To the orthodox economist, money is just money and finance should act upon as those generic assumptions would have it. The complexity of especially eurodollar operations is far beyond the grasp of an entire discipline dedicated to simplifying everything so that covariance matrices don’t exceed the limited computing power of whatever is available at the university. In short, QE is not a straightforward intrusion into “markets” nor should it ever be expected to be so.

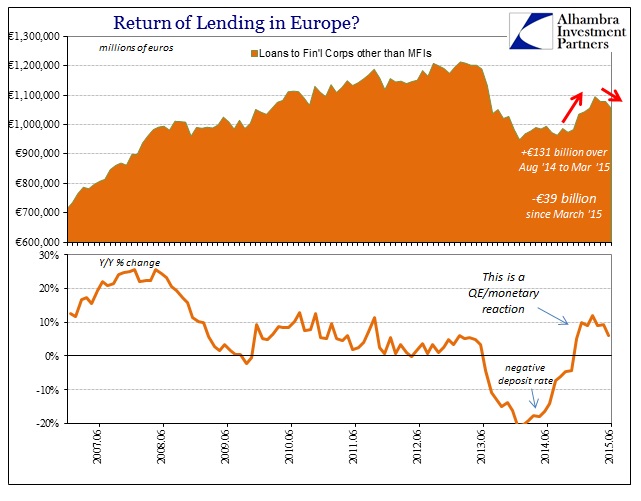

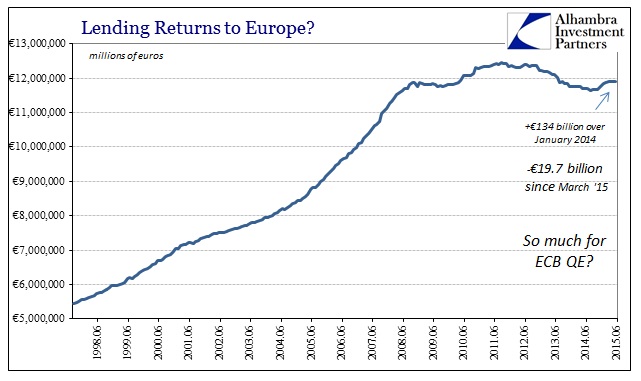

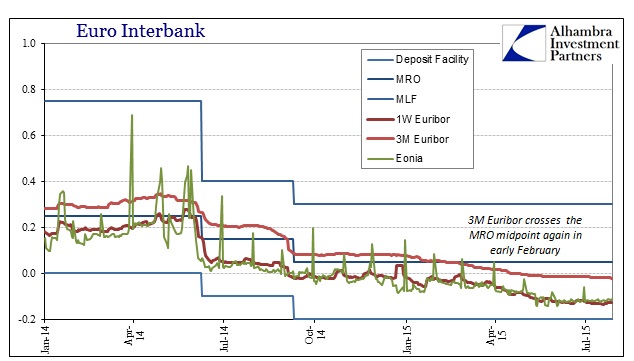

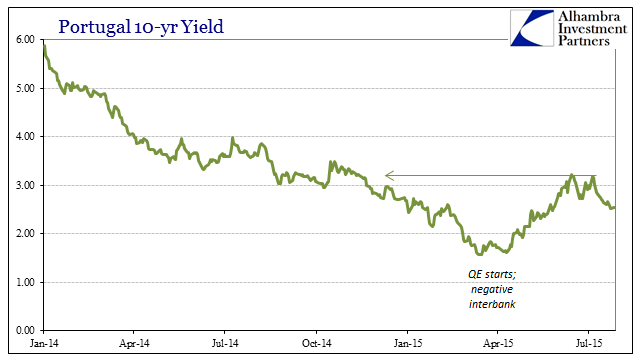

The ECB finally went in on the process back in March. After only a few weeks it was declared a resounding success because there was some assumed lending activity. And that was true, but it wasn’t lending to the real economy as it was limited to non-MFI financials (which is still unclear as to a more specific destination). It is quite curious that lending in this sector peaked at March and has declined significantly since. That certainly seems as if financial firms and institutions were switching around net arrangements in order to profit from whatever the ECB would buy, and have done so without fostering the sustained lending that was not just expected but the only way the ECB has to make anything work.

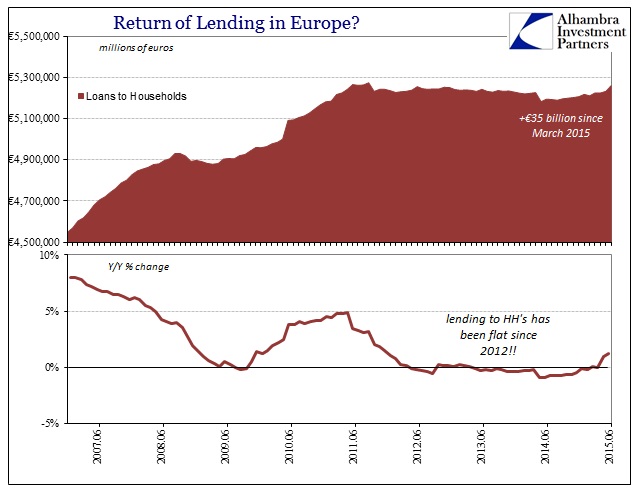

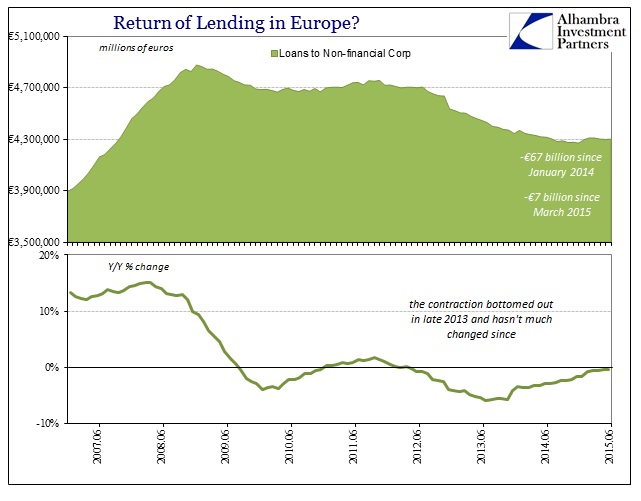

About the only positive that can be claimed so far of QE is that household lending is up slightly since March, though not really significantly (as the flat trend remains). Lending to Nonfinancial corporations is still mired in negativity, having also not much changed for several years now (despite all the prior and now forgotten massive monetary interventions).

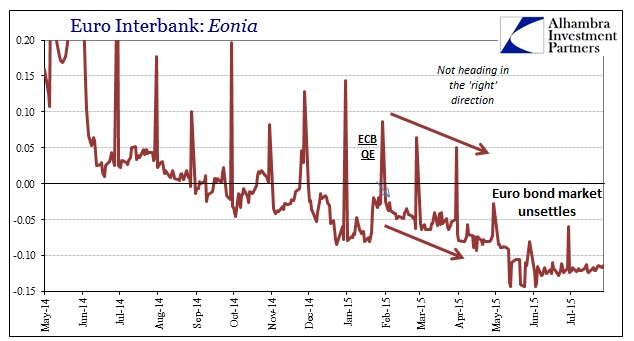

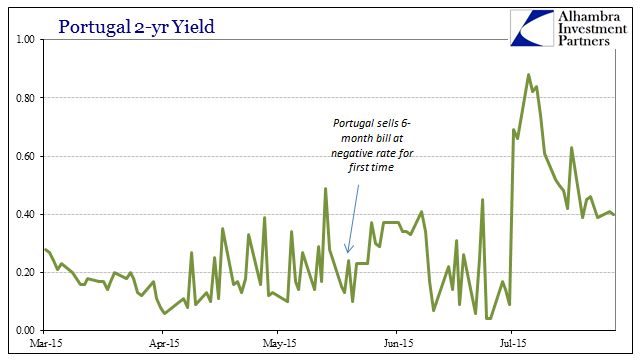

Maybe at some point this all turns around and the full fury of a funded European banking system will be unleashed in a torrent of real economy lending (I highly doubt it, but you never know). That won’t be for some time, however, and there are very real drawbacks to QE already at work. Most prominent and unappreciated is the negativity in the money markets.

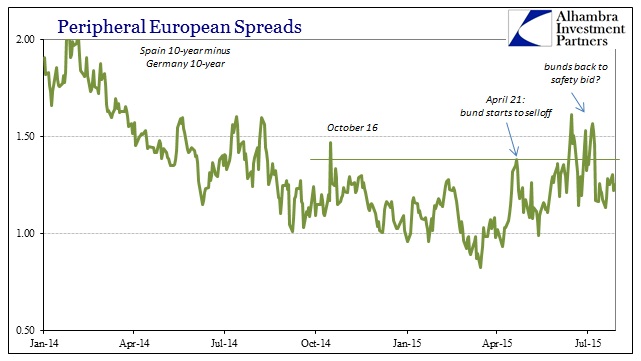

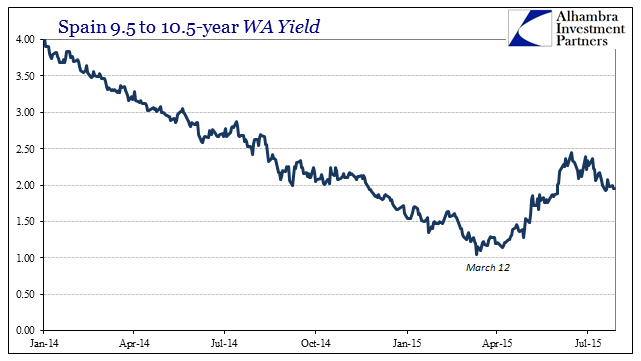

Global wholesale banks, or shadow banks, don’t need any additional reasons to further withdraw from dealer activities, so persistently negative money rates are not going to be at all helpful. Undoubtedly, that is one reason why European bond markets have “suddenly”, under the cover of QE no less, become crapshoots. Greece gets all the blame for that, but underneath the financial surface there is turmoil that all the devised “term premiums” in the world cannot offset.

I think that is why, despite Greece’s apparent “fix” in the past few weeks, European bond markets remain unsettled. There is, of course, still the elements of further Greek uncertainty to factor, but overall the connection between QE-diminished money dealing and bond market volatility if not higher overall yields is quite compelling.

This has been the pattern of QE everywhere it has been tried, as it comes in and blasts apart prior function leaving economists to essentially devise ways in which apparently “worked” since the primary benchmarks are never close to being met. So far in Europe, the money market is awash in harmful negativity already without so much as the needle moving in the intended direction on lending or the real economy (thus the near-panic over the drop in the Eurozone PMI this week). As Japan, the negative effects are rather obvious and upfront while the supposed benefits are either always just around the corner or so unclear as to be a matter of academic study alone.

That is the problem of all types of monetarism, as economics claims it to be neutral under economic terms. But it isn’t neutral in any terms, as the damage to the financial sector is pronounced; and damage to the financial sector will eventually translate into something much, much worse than if QE or monetary intervention had never occurred. That is the lesson of the Great Recession itself, monetarism that is cause of great negativity, and it keeps being repeated so long as QE remains classified, even by the shrillest of pretexts, as stimulus.