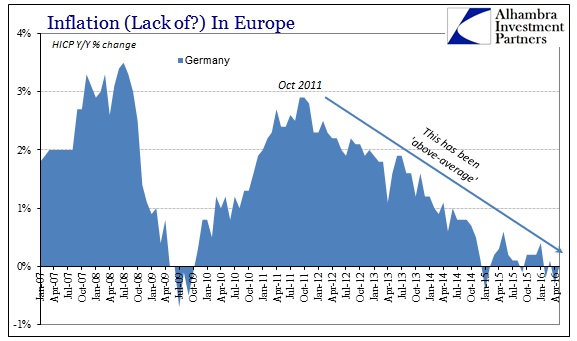

Looking back it almost sounds like a completely different world. In the end, however, the world hasn’t changed, perceptions have. On May 10, 2012, German newspaper Spiegel reported that Bundesbank’s (Germany’s central bank) chief of its economics department, Jens Ulbricht, testified in the German parliament that German inflation was likely to be, “somewhat above the average within in the European monetary union.” What happened after it seems amazing in retrospect.

The Financial Times declared the statement as a regime change for Bubba, saying that, “The willingness to contemplate higher domestic inflation in public comments points to a new-found flexibility in German thinking.” Just two days later, Germany’s largest newspaper Bild ran on its front page a story under the title Inflation Alarm that featured no less than an accompanying picture of Weimar Germany’s 1-billion mark note. Germans may still be more afraid of a return of hyperinflation than Nazis.

And why wouldn’t they be? There was a seeming recklessness in official monetary policy among policymakers who didn’t inspire much if any confidence. The ECB had been wrong at almost every turn, so claiming that it could control any spark of inflation from the very new LTRO expansion was rightly worrisome at least in conventional terms. For the media, there was every hint that central banks might be too powerful for their own good.

That is, of course, the image every major central bank has tried to project since the 1970’s. It has been full circle in almost every way imaginable. In fact, Ulbricht’s contention has largely come true, just not in the way he or anyone else of the mainstream or orthodox (redundant) persuasion ever figured. German HICP inflation was 0.0% in May 2016, thus slightly above the -0.1% for the Eurozone as a whole. For the five months of this year, Germany’s average HICP rate finds the same comparison.

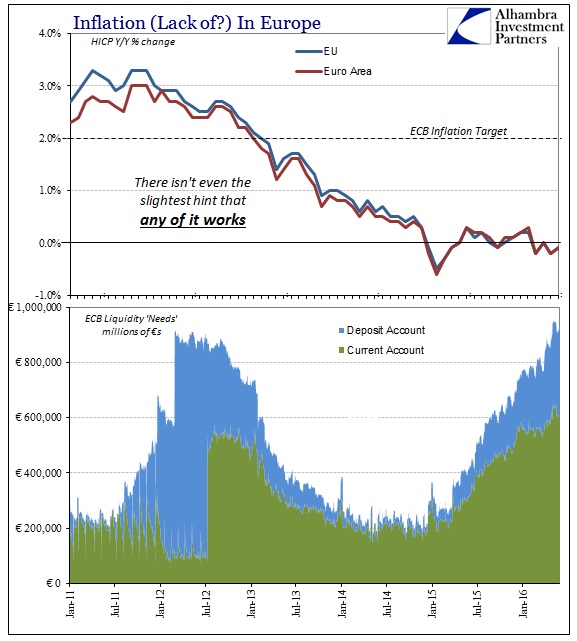

Inflation in Europe rather than firing up the hyperinflation excesses has trended stubbornly in the other direction no matter what. This despite not one but two trillion euro monetary programs that are still both described as both “stimulus” and “money printing.” Rather than being “too” powerful, the rightful and appropriate question is whether central banks matter at all.

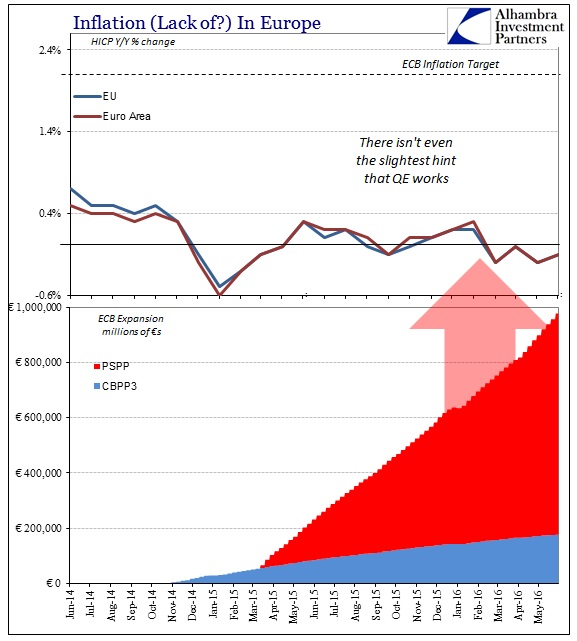

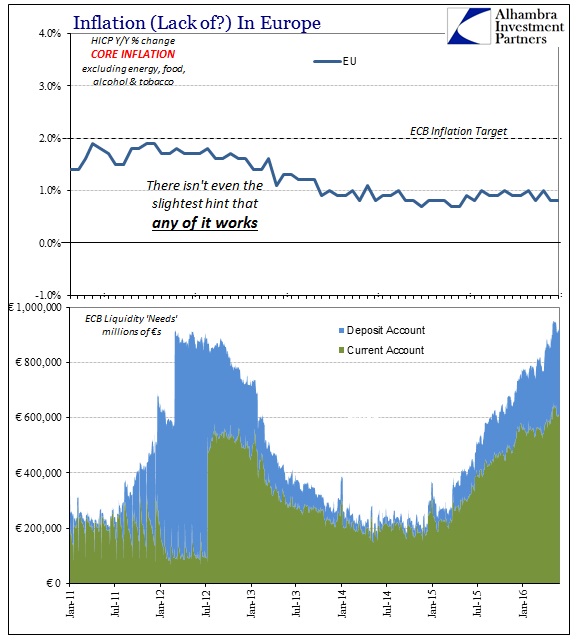

That includes, of course, the QE proposition that was supposed to be a complete “game changer.” Unlike the LTRO’s, which were liquidity expansion, QE was supposed to be that much more powerful as balance sheet expansion. In that regard, the program surpassed a dubious milestone in early June, bringing total purchases to more than €800 billion since it started. Together with the third Covered Bond Purchase Program, the ECB has surpassed €1 trillion in “money printing” balance sheet expansion. And it hasn’t had any effect on European inflation – at all.

Furthermore, it doesn’t matter if you consider oil prices or not; so-called core inflation in Europe has been just as unresponsive as the overall HICP. It’s as if QE, LTRO’s, or whatever the ECB concocts just aren’t there.

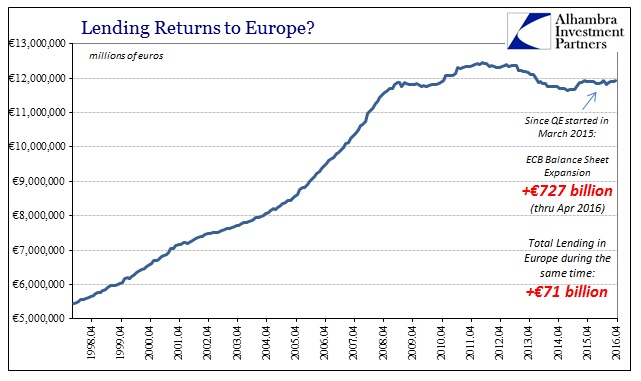

This futility is not just a consumer price “problem” (setting aside the obvious objection as to whether higher inflation should ever be a goal in the first place), as lending in Europe is as much unimpressed. Since QE started in early March 2015, despite almost €730 billion in total bond “purchases” (through April 2016) total lending in Europe has only increased by €71 billion; less than one euro in lending for every ten in ECB foolishness. And almost all of that occurred right at the start last March; not including that one month, total lending has grown by just €17 billion no matter how high the balance sheet piles.

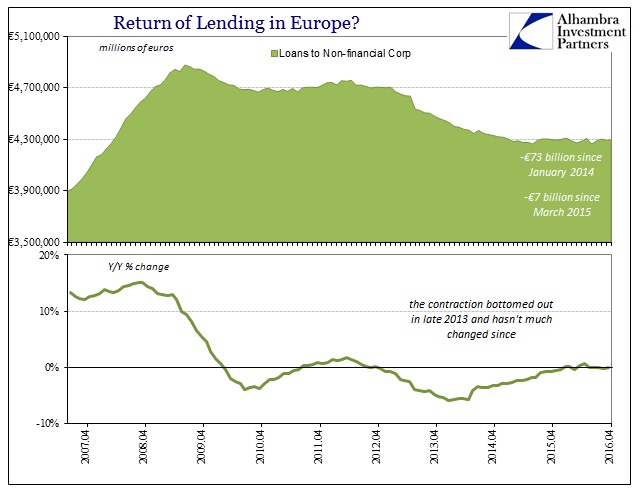

This is true especially in the one segment that is supposed to be the greatest beneficiary and economic transmission – European businesses. Lending to NFC’s (non-financial corporations) has been flat to lower no matter what the ECB does or how it does it; and that means through both periods of “inflationary” effort. There is a level of imperviousness that rightfully reminds anyone of the lack of inflation because that would be the key relationship – expansion of productive activity is what this is all really about.

The only concept the ECB can expand is its own self-regard. What it has done instead is reveal the misconceptions that surrounded monetary policy. The Germans never had anything to fear about the European central bank’s monetary policy or its intentions because it was all fantasy and myth. Like the Federal Reserve, the crisis had the effect of forcing central banks to become explicit agents instead of implicit via various interest rate targets (in Europe in the form of a hard corridor controlled by the ECB policy body).

Rather than proving themselves perfectly capable, or even minimally so in very blunt operations, central banks have instead proved that they were always irrelevant. It only appeared to work before the crisis because, like Germany’s temporary inflation freak-out in 2012, the myth of powerful central banking dies hard. It should have been thoroughly disproven by the events of 2007, 2008, and into 2009, and actually was to those paying attention, but the trauma of the crisis obscured such a genuine reckoning.

So the global economy has lost a decade in deference to the imaginary, the financially fictional. The new monetary science that hopefully replaces these old, controverted ideas should be based in full part on the observations provided above. No matter how “solid” the math that expects correlation between central banks and economic factors, there is none to be found. This point is inarguable no matter how high the ECB (or any of its comrades around the world) wishes to go. Europe is unique in that regard since it has been doubly disproved by actions the mainstream claims were entirely different; so even taken at the word, the proper interpretation is that neither the format nor the scale make any difference whatsoever.

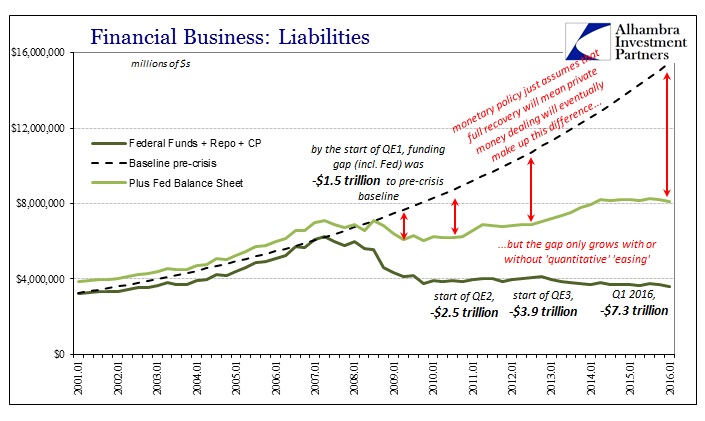

The answers to these monetary questions lay far outside of all this in the global wholesale monetary system. It is a simple piece of recognition – the wholesale system is retreating in much larger scale (by both quantity and quality) than any central bank could achieve. Balance sheet expansion is always framed as if it occurs in a vacuum; it does not. Though the figures provided below (from a full report that will be available to email subscribers first) apply to only the US domestic wholesale financial system, that still provides a window into the processes and characteristics that are all the same for the eurodollar system in what we can’t directly observe. In many ways, we don’t need to (though we should still try); the proof, the answers are all above in establishing what the ECB will never be able to accomplish.

In other words, we don’t need to put a figure or hard location on monetary contraction to know of it because we can easily observe its effects – including the established fact that no matter what central banks do it just disappears into the wilderness of mainstream myth.