On July 14, 2006, the Bank of Japan raised its benchmark overnight rate off zero for the first time since introducing the world to ZIRP in 1999. In doing so, the BoJ noted that the Japanese economy in its view continued to “expand moderately” and that risks inside the economy were “balanced.” The central bank also sought to reassure, further commenting that despite one 25 bps rate hike “an accommodative monetary environment ensuing from very low interest rates will probably be maintained for some time.”

These words, all of them, should sound frighteningly familiar, as they are being redeployed in nearly exactly the same phrasing by the Federal Reserve. Whether or not the FOMC votes for a second rate hike today still remains to be seen, as before that “news” there is first the BoJ once more admitting that its prior efforts didn’t actually work. For the record, Japanese officials actually carried out two hikes, a second coming in February 2007 just in time for the open minded to finally see what really had been going on in the global economy.

In other words, the Japanese policymakers made the same mistakes as are being made today. They assumed absence of further contraction was the same as recovery. In the singularly binary model of orthodox economics, if an economy isn’t in recession it must be growing; so if the economy isn’t in further recession and the economy is barely growing or even stagnating then it is assumed that growth is just being delayed. By the middle of 2006, the Bank of Japan believed there were enough signs the economic postponement had ended.

They took such a stance even though there weren’t many indications quantitative easing in addition to six years of ZIRP achieved anything like their original goals (this, too, should seem eerily recognizable). Writing for the NBER in September 2006, several months after the first rate hike, economists Takatoshi Ito and Andrew K. Rose wrote that the deflationary impulse within the Japanese economy remained. Thus, the Bank should have adhered to its stated purpose:

When the BOJ adopted ZIRP for the first time in February 1999, the condition for lifting ZIRP was when deflationary concerns were dispelled. When the ZIRP was effectively reintroduced in March 2001, the condition became more concrete: excess reserve targeting, or de facto ZIRP, would not be abandoned until the inflation rate, measured by CPI excluding fresh food, became stably above zero.

The Japanese CPI in 2006 ended up barely positive on an annual basis, with the index excluding fresh food even less so. While the Bank of Japan viewed that as a favorable outcome, the CPI both overall and without fresh food would fall back to zero again in 2007. Ironically, it wasn’t until 2008 that Japan saw any measurable inflation as the (temporary) effects of the “dollar” were far more potent than any QE.

What Ito and Rose argued was that monetary policy needed(s) to have a credible target in order to achieve its aims. This remains a common critique of Japanese monetary policy going all the way back to Paul Krugman in the late 1990’s (“credibly promise to be irresponsible”), that though they are willing to try new methods and develop different monetary tools they need also the nerve to commit to them. In other words, though BoJ had committed to positive inflation as far back as 1999 they needed to really commit to inflation.

In the past, the BOJ officials have argued that, because the bank lacked the tools to achieve an inflation target, the announcement of a target would undermine its credibility. There is a certain undeniable logic to the view that announcing a target is futile without the means to achieve it. It is worth stressing, however, that this pessimistic assessment requires either that “unconventional” policies are ineffective (a view that the disappointing experience with quantitative easing has done little to dispel), or that the ZLB will always bind.

There is so much truth in that passage, but not in the way its authors believed. This relates to the BoJ policy action today where the Bank finally took that extra step. Echoing Mario Draghi in July 2012 (an ominous chord to start with), monetary policy in Japan is now committed to doing whatever it takes including messing with the yield curve until the CPI is above 2% and the economy demonstrates sufficient positive conditions such that it will remain there. If you are hearing that for the first time it might sound confident and new, but it is really the same commitment that Japanese officials made in 1999 only substituting 2% for zero.

This is undoubtedly one of the effects of the gathering of central bankers last month in Jackson Hole, though not specifically limited to that conclave. A significant amount of chatter and even literature clinging to this idea has been building this year in the wreckage of QE. Central bankers have been forced to come to terms with that, reluctantly, and so even though there isn’t yet a consensus on what to do next a great many of them believe that, like Japan in the early 2000’s, the answer lies in deeper commitment paired with still more policy tools.

In other words, Japanese officials are still viewing their failure in terms of the first part of the second passage I quoted above – lacking the “tools” they don’t want to commit to a target. In light of everything that has been done especially in Japan over the past eight years, there really is no limit anymore so the Bank can go wherever their hearts might desire. But they are still doomed to fail because the answers all lie in the second part of that quote. The “pessimistic assessment” of a futile target does, in fact, arise because “unconventional policies are ineffective.”

In that way, the Bank of Japan has performed an invaluable service to the world, though it will be quite some time before the mainstream is reformed sufficiently to appreciate it. By being willing to experiment in all ways, types, and sizes, BoJ has proven that supposition; no matter what they do, they cannot achieve their goals. Even the latest policy is an admission that prior policies failed, most especially NIRP (a primary purpose of the yield curve “target” is to undo some of the damage caused by negative rates). As I have written for years, it can’t be “quantitative” easing if you have to do it repeatedly.

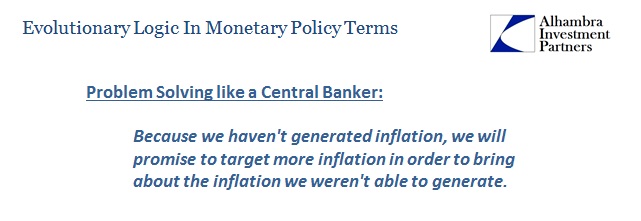

Central banking has simply devolved further into Monty Python-esque territory. This potentially renewed commitment to forward guidance is laughable pop psychology passing for a coherent understanding of money and economy. They started out by believing that the public view of ZIRP would be so awed as to kickstart inflation and thus economy on its own (expectations). The public was awed for a few months and then went back to the same. They added “quantitative easing” to ZIRP as an additional “awe”, and again after a few months the public went back to the same. So QE was repeated, only bigger, and you get the picture.

An actually rational human would view all that and conclude that QE and ZIRP just don’t work. A central banker views all that and concludes that if what is supposed to work on its own doesn’t then the central bank must promise to keep doing what doesn’t until it does. That is where we are in 2016, where satire and farce are all that is left. It is, unfortunately, a tragically fitting critique because the orthodox belief in control was satire from the start, now openly revealed for what it always was.

It will be left to future historians to stand in amazement that this was allowed to go on for so long without straight up revolt. The Bank of Japan has proven in every way possible that they really don’t know what they are doing. And yet, they are still being permitted to do it.