Debt.

Everyone understands it pretty well when it comes to their personal finances. You borrow money, you have to pay it back. If you can’t, your creditor hounds you until you either come up with the cash or restructure your repayment schedule. Or, worst case, you eventually file for bankruptcy, thereby defaulting on your debt. Simple.

Yet people, especially in the West, seem blithely unaware that the same basic principles apply to countries, as well. Most of us tend to think that nations can’t or won’t default on their debt. Well … maybe Greece will. But surely not a big country.

Why we believe this is partly due to an ignorance of history, which features literally countless defaults, among nations great and small. Even the US has done it. More than once. It happened right at the beginning, in 1779, when the fledgling US nation defaulted on its first currency, the Continental (which led to widespread use of an early American pejorative phrase: “not worth a Continental.”) And a very recent example was when Nixon severed the tie between gold and the dollar in 1971; that was a default on the precious metal debt the country owed to France and others.

It’s also partly due to the current financial behavior of the American government, which acts as if the cure for a debt problem is more debt (do not try this at home, by the way). As Congress raises the federal debt ceiling, and the Federal Reserve creates ever more currency units out of thin air, it creates the illusion of stability. All it’s really doing, though, is just kicking the can down the road. The US has placed itself firmly on this path. But that doesn’t ensure that the rest of the world’s nations can or will follow the same one.

Particularly Russia.

In 2014, I published The Colder War, which became a New York Times Bestseller. Vladimir Putin, Russia, oil and energy were all dissected in my book, which today is every bit as timely as it was when I wrote it in 2013. Because of the decade I spent researching the book, I have a very unique Westerner’s perspective on Russia.

Here’s one of the things I learned: Russia is completely unafraid of a default on its debt.

Russia was a basket case in the 1990’s. The first war in Chechnya was a disaster, both economically and psychologically for the Russians. Russia not only lost that war, it had a disaster of an economy, ran a huge governmental budget deficit, and was stuck with a very unfavorable fixed exchange rate between the ruble and the currencies of all its trading partners. The country was barely staying afloat.

Then, on top of all that, came the two additional straws that finally broke the Bear’s back: the Asian financial crisis and a crash in oil prices.

But the West totally mis-guessed the eventual outcome. The World Bank and the IMF arrogantly assumed the Russians would continue to play by their rules. In fact, years later it was leaked that billions in IMF relief funds had headed east, where they were “misplaced.” Or, in laymen’s terms, stolen before they even hit the Russian bank accounts.

On August 17, 1998, the so-called “Russian flu” infected world markets. Moscow announced that a moratorium would be placed on payments to foreign creditors. In addition, the ruble was devalued by 33% (from 7.1RUR/USD to 9.5RUR/USD). Within a few months, the government allowed the ruble to float freely and the currency devalued by another 120% to 21RUR/USD. There were bank closures, political fall guys and rabid inflation.

The Russian oligarchs, many of them ruthless criminals, made their moves—and consolidated their wealth at levels that would make the American robber barons blush.

Into this chaos, in 1999, entered Vladimir Putin—one of the most mischaracterized politicians on the planet. An archetypal Russian strong man, he brutally squashed the Chechen revolt and moved decisively to bring the oligarchs under state control, which meant killing or imprisoning them, or driving them into exile. Most importantly, he committed massive resources to reviving an energy sector that had fallen into disrepair, and made it quasi-public with companies headed up by his buddies and inner circle. As prices moved upwards, Russian crude oil output expanded like crazy to become #1 in the world and the economy boomed, as did Putin’s global agenda.

Through a series of deft political maneuverings, Putin still controls Russia 16 years later. During that time, he has stayed enormously popular among his countrymen despite policies that Westerners (and some dissenting Russians) find reprehensible. His prolonged supremacy is quite a feat, given how the byzantine nature of Russian politics laid low any number of his predecessors. But he’s done it by persuading the mass of the people that he always acts in what he sees as the best way to push Mother Russia to the head of the table among nations, and that in that pursuit he’s willing to let all manner of chips fall where they may.

Today, Russia is in crisis again, having been hit with the double whammy of plummeting energy prices and heavy sanctions laid on by the West over Putin’s foreign policy. Given the country’s struggling economy, it’s puzzling why the world is ignoring the risk of Russia defaulting on its debt. Again. And why it may be underestimating Putin. Again.

Why a Russian Default is a very real scenario in 2016

The IMF is loaning billions to Ukraine. In addition, NATO is spending billions in Ukraine on a war that has lasted longer than any US or NATO official expected. The West, led by the US, has put national sanctions on Russia, and personal ones on many of Putin’s associates—despite a clear historical record that shows sanctions almost never achieve their stated ends.

To understand how misguided this is, you just have to ask one question: Who holds the majority of the debt that would be at risk in a Russian default? Not China. Not Iran. Not Syria. No, it’s the exact same nations, and banks and funds within those nations, that are applying the sanctions against Russia.

So, if Russia does default, what does it mean in terms of its political relationship with the West?

Nothing.

But what does it mean to its creditors?

Everything.

They’re the ones who will take the hit. And by the way, to anyone who thinks they will be able to enforce their nation’s debt laws on the Russian government or any Russian companies, I have this to say: I wish you the best of luck.

Don’t buy my story?

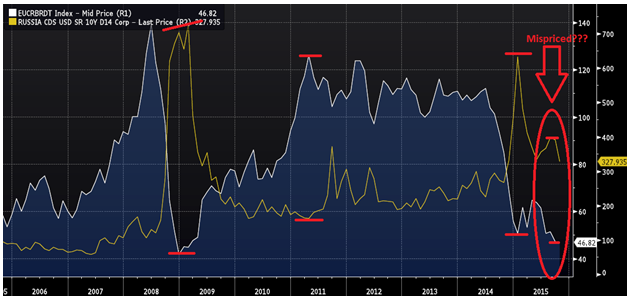

Here is a chart of Brent Oil pricing verses the 10-year Russian credit default swaps (CDS).

The market is completely mispricing the Russian CDS, by totally ignoring the potential for a Russian Default.

For comparison purposes, in the oil crash of late 2008 early 2009, Russian CDS popped 600% to over 7%. (The CDS market can be a bit complicated, but in general terms, the higher the rate, the more perceived risk is being priced into the market.)

Even earlier this year, with the Brent price of oil trading higher than it does now, the CDS were 100% more expensive. But they’ve since fallen to around 3%, which is absurd, as oil is lower now than when the CDS were at 100% higher rate—therefore if the market was paying attention, CDS should have a “higher” rate now than earlier this year.

The market is assuming that Putin will play by the western bankers’ rules; therefore there is no fear that the Russians might default on their debt.

Otherwise, there’s no reason Russian CDS would be 50% lower than earlier this year, given the fall in the price of oil, which is critical to their economy.

Has something else changed?

Are we in some better place globally now? I highly doubt it for many reasons, but how about I just mention one horrific fact: the world has never seen more displaced persons—ever— than we currently have at over 60 million.

Or has Putin merely distracted the Western world by diverting its interest to Ukraine and Syria?

Those are relatively small items on Russia’s policy agenda. Putin’s real focus is on strengthening his country’s economy by ramping up business with China and the emerging markets. That is where the future lies. If Putin can’t entirely eliminate all dependence on the West, he’s certainly moving forcefully to greatly diminish its influence.

The $400 billion natural gas deal he signed with China in 2014 is just one powerful indicator.

In a few words, if Putin believes that the benefits of a default outweigh the consequences to his country, he won’t hesitate to do it, no matter the international ruckus it might raise.

So … my advice is that if you are invested in any funds or banks that are exposed to debt in Russia, I would rethink your investment thesis. The rules of the game are apt to change quickly, and not to the foreign debt holders’ benefit.

And, if you like ironic coincidences, I’ll close with this one.

Donald Trump is the current leader for the Republican presidential nomination. During his business career, he’s helmed four companies that filed for Chapter 11. Which just happens to be the same number of Russian bankruptcies that have occurred during ‘The Donald’s’ lifetime.

Who knows, ‘The Donald’ and Putin might end up the best of friends…

Source: Why Russia May Default on Its Foreign Debt – Katusa Research